A crippling joint disease

The term

elbow dysplasia (ED) is a general term that is used to describe a developmental degenerative

disease of the elbow joint. Understanding the symptoms and causes of ED is extremely important

if informed decisions are to be made regarding diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of ED. The

Working K-9 Vet Dr. Henry de Boer discusses this crippling disease, its causes and symptoms and

diagnosis along with its treatment and prevention. The term

elbow dysplasia (ED) is a general term that is used to describe a developmental degenerative

disease of the elbow joint. Understanding the symptoms and causes of ED is extremely important

if informed decisions are to be made regarding diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of ED. The

Working K-9 Vet Dr. Henry de Boer discusses this crippling disease, its causes and symptoms and

diagnosis along with its treatment and prevention.

Question?

I have been hearing a lot about elbow dysplasia

recently. What exactly is elbow dysplasia? Are there symptoms I should be watching for in my

young dog?

Answer...

There are in fact three different etiologies that can

create a diagnosis of ED. These etiologies may occur individually or in combination with each

other in any one dog. This disease has created considerable confusion and controversy not only

on the part of dog owner, but with practicing veterinarians as well as researchers who are

studying the problem. While our ability to diagnose ED has improved in recent years, there is

still a great deal to be learned about its causes, prevention, and what constitutes appropriate

treatment.

ED occurs predominantly in medium or larger breeds of

dogs. The Orthopedic Foundation for Animals (OFA) maintains statistics in their elbow registry

for many breeds. As of December 31, 1998, ED had been diagnosed by OFA in 87 breeds. Incidences

range from 0% in Border Collies up to 47.8% in Chow Chows. The average incidence of the breeds

for which at least 75 individuals have been evaluated is 11.11%. Male dogs are more likely to

have ED then females, and 20-35% of dogs with ED have it in both elbows.

Dogs with ED may or may not be lame, therefore, using

lameness to determine its presence or the breed worthiness of an animal is foolhardy. Dogs with

clinical ED typically develop foreleg lameness between the ages of 5-12 months of age, however,

in some cases the lameness may not be apparent until as late as 5-7 years of age. The lameness

may be variable and periodic. Some dogs may demonstrate soreness after rest, improve slightly

with activity, but then worsen with increased activity. There may be intervals with no lameness

at all. Jumping and sharp fast turns usually exaggerate the lameness. Pain can be elicited by

overextending the elbow, and there may be a slight to moderate swelling noticeable when

carefully feeling the elbow joint. If both legs are meaningfully affected the lameness may be

more difficult to detect. Careful observation would show slight rotation of the top of the paws

outwardly, as well as a stiff or stilted movement of the forelegs. There may be a reluctance on

the dogs part to land hard on the front legs (e.g. trotting, loping or landing jumps).

For the sake of

simplicity the three etiologies resulting in ED will be discussed individually, but it is

important to note that there can be considerable overlapping in their presence, their cause and

effect. The magnitude of the overlapping has probably not been fully realised at this time. For the sake of

simplicity the three etiologies resulting in ED will be discussed individually, but it is

important to note that there can be considerable overlapping in their presence, their cause and

effect. The magnitude of the overlapping has probably not been fully realised at this time.

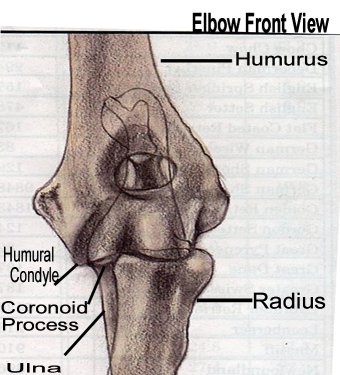

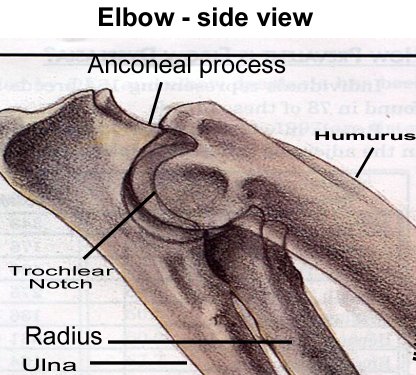

The anconeal process is a small pyramid shaped

piece of bone on the upper end of the ulna. In a young dog, it is a piece of cartilage that

gradually turns to bone and unites with the rest of the ulna at approximately 4 ½ - 5 months of

age. If that union fails to take place we have an ununited anconeal process (UAP). The presence

of UAP leads to degenerative joint disease as a result of a decrease in stability within the

joint, and an increase in inflammation caused by the chip of bone being free within the joint.

Osteochondritis dessicans (OCD) can occur in many joints,

but when it occurs in an elbow it most commonly is on the lower, inner aspect of the humurus

(medial humural condyle). In essence OCD is a vertical fracture in the articular cartilage of

the humurus, which can lead to a flap of cartilage within the joint. This flap leads to

degeneration within the joint as a result of an inflammatory process.

The

coronoid process is a small piece of bone on the ulna, which articulates with the humurus.

Similar to the anconeal process it starts as cartilage, and gradually turns to bone as it

unites with the rest of the ulna. Failure of that fusion to occur or chipping of the area after

fusion has occurred, creates a fragmented coronoid process (FCP). Subsequent to FCP

degenerative joint disease develops for the same reason as with UAP. The

coronoid process is a small piece of bone on the ulna, which articulates with the humurus.

Similar to the anconeal process it starts as cartilage, and gradually turns to bone as it

unites with the rest of the ulna. Failure of that fusion to occur or chipping of the area after

fusion has occurred, creates a fragmented coronoid process (FCP). Subsequent to FCP

degenerative joint disease develops for the same reason as with UAP.

Causes

The exact causes of ED have been the subject of considerable controversy. A number of

predisposing factors have been identified, and recently some new theories have gained support

as probable explanations for the development of ED. The individual etiologies of ED most likely

have multiple possible causes.

OCD has at least three possible causes.

- Heredity certainly plays a role, as we do see a

tendency for this problem to occur in family lines, as well as in those breeds that grow

rapidly.

- Trauma within the joint also is a factor, evidenced by

the fact that areas commonly affected by OCD are those that typically experience high levels

of biomechanical stress. Additionally, animals housed on hard surfaces are more likely

statistically to have a higher incidence of OCD.

- A third cause is a lack of sufficient blood supply to

the joint cartilage. The specific cause of this marginal blood supply is not currently

understood.

Understanding of the causes of FCD and UAP has

experienced a surge in recent years. In addition to the causes listed for OCD, recent research

strongly suggest that two factors are playing a major role in the development of these two

etiologies. A disparity in the growth rate between the radius and ulna, as well as an abnormal

formation of the trochleor notch in the ulna, have been implicated in the development of ED.

The elbow joint is a very complex joint that is created by the junction of three different

bones. Normally these bones fit and function together with very close tolerances. If the growth

rate of the bones is changed, or a structure does not form normally, the tolerances change,

enhancing the possibility of damage within the joint. The damage created typically results in

either FCP or UAP.

Diagnosis

The term elbow dysplasia (ED) is a general term that is used to describe a developmental

degenerative disease of the elbow joint. There are three component causes:-

- Osteochondritis dessicans (OCD)

- Ununited anconeal process (UAP)

- Fragmented coronoid process (FCP)

In general elbow dysplasia should be suspected as a

possiblity with any foreleg lameness that persists for more than several days, especially if

the dog is of a breed that may be prone to ED. Examination of the leg yields pain on palpation

when the elbow joint is over-extended. The next step in establishing a diagnosis is having high

quality radiographs taken. Multiple views of the leg should be taken, and if ED is evident,

radiographs of the other elbow are appropriate given the possibility of this problem occurring

in both elbows. UAP is easily detected with radiographs, and in most cases, a diagnosis of OCD

can be made with radiographs as well. FCP can be diagnosed in most cases with radiographs, but

can be a challenge in yet other cases. The problem is that the coronoid process is a relatively

small piece of bone that in the majority of standard radiographic views cannot be visualized by

itself, but rather is superimposed on the other bony structures within the elbow. Given that

superimpositon, if the lesion is small, it may be difficult if not impossible to see. In many

of the cases in which the coronoid process cannot be visualized there will be bony changes in

other areas of the joint that will strongly suggest FCP. If the information from the

radiographs is equivocal, a CT scan can typically help significantly in establishing a firm

diagnosis. While CT scans are not readily available in all local areas, they are generally

available at least regionally, and are a very valuable diagnostic tool for this problem.

The approach to diagnosing ED is consistent, however the

approach to treating the problem is variable. Developing a treatment protocol for ED depends

not only on the etiology, but also on the symptoms that the dog is demonstrating, as well as

the duration of the problem.

Treatment

UAP traditionally has been a problem that has been treated surgically. In the past, one of two

surgical options have been used. In the first, the fragment of bone within the joint has been

removed, and in the second, the fragment has been reattached using a lag screw. In general,

dogs undergoing either of these surgeries have improved to an extent clinically, but in many

cased, degenerative joint disease continued to develop and there is typically some loss of

stability within the joint and/or some sporadic lameness. For working dogs these results have

been less than impressive. Recently a new surgical approach to the problem has been developed,

in accordance with the theory that a disparity in growth rates between the radius and ulna is

to blame for the development of the UAP. In this surgery a small slice of bone is removed from

the ulna, which prevents the disparity in growth rates from creating tension within the joint.

This decrease in tension allows the anconeal process to unite, followed by healing of the ulna.

Early reports from those surgeons using this technique have been extremely encouraging. In a

high percentage of these cases the anconeal process is uniting, there is minimal degenerative

change and no instability within the joint. This procedure, in my opinion, is very promising

for our working dogs. It is important to note that for this procedure to be beneficial the

problem must be diagnosed as soon as possible. The anconeal process, in most dogs unites

normally at approximately five months of age. Radiographic screening can be done at five to six

months of age, and, in most cases no sedation or anesthetic would be necessary for the

radiographic view required.

Treatment of FCP or OCD can be medical or

surgical/medical. I typically recommend that most dogs with FCP or OCD be treated medically at

first, and if the results are not satisfactory, surgery should be considered. Medical

management would include a moderate exercise restriction as well as a dietary change if

warranted. The dietary alteration would be to achieve weight reduction if required and to alter

food intake so as to keep growth rate at a relative minimum. The use of chondroprotective

agents such as Cosequin, Glycoflex or similar products is appropriate, as well as the use of

non steroidal anti-inflammatory medications. If after five to eight weeks, the results of

medical management is not satisfactory, surgery can be performed. The surgical technique for

both FCP and OCD essentially results in removal of the adversely affected area. Surgery should

be followed by the ongoing administration of chondroprotective agents and anti-inflammatory

medication if required.

The results of surgical/medical management are generally

satisfactory, with some animals experiencing substantial relief but some others showing only

moderate improvement. The prognosis for a working dog that has had surgical repair for FCP or

OCD being able to work pain and lameness free is fair, and there is a moderate probability of

early degenerative joint disease (arthritis).

Prevention

Prevention of elbow dysplasia can indeed be a frustrating endeavor. While some of the causes

are known, the level of understanding as to their relative importance, and how they relate to

each other is still being examined. The primary factors we need to be conscious of are:

genetics, nutrition, and trauma.

ED clearly has a genetic basis, however, it is not highly

predictable as to which dogs will be affected by its presence. This lack of predictability

eliminates our ability to confidently select breeding stock or puppies it they are from a breed

that is predisposed to ED. In spite of this low level of predictability, every effort should be

made to eliminate this problem. The Orthopedic Foundation for Animals (OFA) does have an elbow

registry that will certify elbows at two years of age. They will give preliminary evaluations

at any age, and given the surgery available for UAP, screening at five to seven months of age

would certainly be prudent. Any dog with radiographic evidence of ED, whether or not they are

lame, should probably be eliminated from breeding. It is important to note, however, that dogs

with low level changes in an elbow (Grade 1 ED) may never develop any lameness whatsoever.

Working these dogs is appropriate as long as the handler is mindful of the possibility of a

future lameness. Clearly, if these dogs are being worked, weight should be kept at an

appropriate level, and those exercises requiring hard landing on the forelegs should be

minimized. Additionally, dogs with very low level changes on a preliminary evaluation should be

re-evaluated in six to twelve months. Changes in an elbow that appear significant at a young

age may be insignificant at an older age a long as there has been no progression in the

changes. These dogs could potentially be clear of ED at a mature age.

Nutrition has also been shown to play a role in the

development of ED. The specific factors that have been shown to be of particular consequence

are the feeding of high energy foods, especially if fed in excessive volumes, and the level of

calcium in the diet.

Rapid growth has been shown to increase the risk of ED.

Every effort should be made in those breeds predisposed to ED to keep their growth rate as low

as possible by keeping food volumes as well as the energy content low. A higher energy content

of a diet increases the likelihood of a dogs consumption surpassing its requirements. Since fat

is a substantial component of energy density, fat content of a chosen diet for young dogs

should generally be below 17%. Total energy density should be kept below 4.0 kcal/g. This

information should be available from the manufacturer of the food.

For many years it was felt that the ratio of calcium to

phosphorus in a diet was more important than the absolute volumes. This has been shown to be

inaccurate, and current recommendations are that calcium levels should be approximately .9 –

1.5% on a dry matter basis.

In recent years there has been a tremendous surge in

nutritional supplements for dogs. Inasmuch as ED is concerned (as well as other skeletal

developmental abnormalities) supplementation has the potential to create far more problems than

it can prevent. Beware!

Trauma to growing and developing joints can also play a

role in ED. Quantitating the effect of trauma is difficult at best, but common sense would

suggest that while we want to keep young dogs in good physical condition, we should minimize

those activities that would create high impact on developing joints.

Clearly, ED is a complex entity which much has been

learned about in recent year, but much more needs to be done if we are to decrease its

frequency, as well as its effect on our dogs. Hopefully, the increased awareness of ED on the

part of dog owners, as well as continued veterinary research will lead to a significant

decreases in the frequency and severity of this nagging problem.

OFA (Orthopedic Foundation for Animals) is looking for a

former competitor (any breed, actually) who may have been videoed running an agility course

healthy, who subsequently developed ED. They are putting together a film about ED, and the

purpose would be to demonstrate the impact of the disease on competition. A dog living near St

Louis would be ideal, as they might want to include a snippet on the current condition of the

dog.

If your current or former partner fits this and you would

like to participate, contact Ann Green on algreen@panix.com.

Dr.

Henry De Boer is the Working K-9 Vet. Following

his 1973 graduation from Cornell University, he established Pioneer Valley Veterinary Hospital,

based in western Massachusetts. Dr.

Henry De Boer is the Working K-9 Vet. Following

his 1973 graduation from Cornell University, he established Pioneer Valley Veterinary Hospital,

based in western Massachusetts.

His involvement with working dogs dates to the mid-1960’s

when he began training and handling hunting dogs. In 1984 he became involved with the sport of

Schutzhund and has gradually risen to the level of national competitor.

Through the years. De Boer has worked both in a training

and veterinary capacity with a wide variety of working dogs. His knowledge and enthusiasm for

working dogs led to the establishment of Working K-9 Veterinary Consultation Services. This

service provides veterinary consultations for working canines and is available by phone, fax,

or email.

Tel/fax: (+01) 802-254 1015. Or visit http://www.workingk-9vet.com

Picture credits: Orthopedic Foundation for

Animals and Gheorghe M. Constantinescu DVM

Comment:

Here's a totally anecdotal personal experience. (I'm not a veterinarian.)

When I adopted my BC at five months of age, I had his

hips x-rayed without anesthesia. His hips deemed fine at that time.

He became acutely lame in the rear at around two years of

age, and I had him x-rayed again under anesthesia. He was mildly dysplastic. I went into a

tailspin, because I'd already had some pretty nifty wins with him in Novice obedience and was

afraid he'd never be able to jump in the Advanced classes. At that time, I didn't know a single

dog who'd had hip surgery that I considered sound enough to jump. That has changed since then,

and I know lots of dogs who could do obedience jumping after surgery.

Then I got lucky.

A good friend sent me literature on CHD that (I think)

had been put out by the national Labrador club on CHD based on findings by OFA. One thing it

said was that many mildly dysplastic dogs experience acute lameness at around two years of age.

Even with no treatment at all, many of them adjust to it and show no lameness for many years

afterward.

When I told my vet that I was dubious about hip surgery,

he said that he'd recommended one hip surgery in 15 years of practice. He said that proper

exercise to maintain rear-end muscle tone and joint supplements kept all but the most extreme

cases pain-free well past their middle years with no restrictions on their performance

activities. (This was before agility came on the scene, co I can't tell you he'd say the same

today.)

Jack went on to earn his CDX and run in sheepdog trials

until he was nine years old. He's 11 now and still exhibits no lameness in his retirement. He

was diagnosed with moderate dysplaysia in both hips at two.

So here's my advice for what it's worth:-

Don't panic.

- Don't opt for surgery without an independent second

opinion. Keep in mind that surgeons will always suggest surgery, because that's what they do.

- Don't panic.

- Be dubious about surgery when your pup may just be in

an acute phase.

- Don't panic.

- Spay or neuter your dog to help clean up the gene

pool.

- Don't panic.

IOW, don't panic. This may not be the end of the world.

Margie English (USA)

My two cents in about running agility

with dogs who have HD and/or bad elbows...

For those that choose to run a dog with no

obvious clinical signs, so be it...

I, on the other hand, x-ray my GSDs from stem to stern

every couple of years, and if they ever showed the slightest dysplasia, they're done. I

agree muscle mass certainly helps cushion those hips, dogs may never limp or come up lame and

live to a ripe old age with HD, but I don't understand WHY anyone would want to continue

running a dog despite this?

I imagine it can be very heartbreaking to have competed

with a dog and gotten him just where you are happy only to find out they have HD or bad elbows.

Unfortunately, that can be life. I just would never want to put my dog at further risk, and I

truly believe that's what can happen by continuing. I don't see many dogs competing that have

obvious signs of problems, but there are a few, and I gotta say, it's heartbreaking to see them

doing their all for their handlers/owners despite their obvious problems.

Agility is a sport that can be physically challenging on

everyone including the dogs. It just boggles my mind that anyone would be proud of the fact

that their dog can still compete with HD or bad elbows - or would even want to! And I'm talking

downright flunking OFA ratings.. Our dogs (or at least mine anyway) and I'm sure most others,

will do anything most times, to please their owners, but would I ask my GSD to compete in

agility knowing she was dysplastic? No, I wouldn't ask it of myself let alone my dog. Just my

humble opinion.

Diane M. Stevens (USA)

A

plea to two groups of people from Matt Tovey... A

plea to two groups of people from Matt Tovey...

Breeders: Please make dysplasia tests, and

don't breed dogs with bad scores.

Dog-owners: Please check a puppy's parents

hip-scores before buying a dog. You can save yourselves and your dog so much pain...

We took our BC Jess to the Munich veterinary clinic where

they took another very good quality x-ray and an orthopedic specialist examined her. Despite

having stopped agility and having given her medication and supplements, the specialist could

see a worsening of Jess's arthritic condition in just one month. He's advised us to stop

agility, and we will take his advice.

In preparation for German agility last year, we trained

for an obligatory obedience test. As Jess grew confident in her obedience work, she came to

enjoy that. So we plan to get her more into obedience.

It's also been very hard to see our little athlete being

crippled so, but Jess will get the best life that we can give her. We will continue to do

agility with Asterix, although trials are going to be complicated. I hate the idea of taking

Jess along, just to watch.

To read Matt & Jess' story, see

Euro-Agility.

Go top Go top

|