Isaac Newton and

all that jazz...

At

first glance you could be forgiven for thinking that agility judge and keen

observer Alan Waddington has lost the

plot, but I urge you to read this series of mini-articles. They might make you change the way you read an

agility course even if it does not make your financial investment decisions any

easier. So hold onto your hats... here we go. The Isaac Newton Dog Training

Academy presents the impact of the laws of nature on dog agility. At

first glance you could be forgiven for thinking that agility judge and keen

observer Alan Waddington has lost the

plot, but I urge you to read this series of mini-articles. They might make you change the way you read an

agility course even if it does not make your financial investment decisions any

easier. So hold onto your hats... here we go. The Isaac Newton Dog Training

Academy presents the impact of the laws of nature on dog agility.

Dog Agility

An Objective or Subjective Sport?

At

the age of 18 I left school and was indentured as an articled clerk to a

Chartered Accountant in Skipton, North Yorkshire. My parents had signed away my

life for five years. I do not remember having much say in the decision. My

Principal did his best to convert me into a worthy member of the profession. At

the age of 18 I left school and was indentured as an articled clerk to a

Chartered Accountant in Skipton, North Yorkshire. My parents had signed away my

life for five years. I do not remember having much say in the decision. My

Principal did his best to convert me into a worthy member of the profession.

One of the things which he drilled into me

was differentiating between fact and opinion. You have only to read a newspaper

or watch a news bulletin closely to realise that much of what we take as fact is

really opinion or interpretation. It might surprise you that much of what goes

into a set of business accounts is also opinion. More recently the issue has

received great prominence in the debate about 'fake news.'

When I was young, I vowed that I would never

get involved in a sport which involved interpretation of the rules to decide the

winner. Figure skating, ice dancing, gymnastics and diving are all examples of

panels of judges expressing a view on a performance by the score they give.

Sometimes there can be quite a disparity in the scores, usually with the home

country judge giving a higher mark – not the British judge though. We all know

that we are above that sort of thing!

Thank goodness then that I eventually

drifted into dog agility.

It was all about getting your dog onto contact zones, not knocking down

jumps, not refusing jumps, going the right way and not helping your dog by

touching it. This converts into 'Faults', 'Refusals' and 'Eliminations.' It all

seemed straightforward. Performance would be judged by objective measures. Why

then, can I hear my Principal's voice echoing from over 50 years ago? 'The

facts... examine the facts.' I did. He had that sort of effect on me.

Right then, let's get down to business. How

factual is the marking of dog agility? From time to time, judges will make

errors of fact. An example might be a borderline decision on whether a dog got a

contact or didn’t. If judges are unsure, they usually give the dog the benefit

of doubt. In the absence of video replay evidence, there is no way of checking

if an error of fact has occurred, although you do have ringside recordings by

partners or friends, some of whom will gladly tell the judge that they got a bad

call.

Regrettable though these errors are, it is

almost inevitable that, during a full day's judging, mistakes will happen. Most

judges that I know, do everything they can to maintain their concentration and

minimise such situations occurring, and I do not know of any judge who would

deliberately 'sabotage' a competitor's run.

What I want to concentrate on are the areas

where agility judging may stray from marking of fact to making opinions about

what the dog may or may not have done. Three areas spring to mind:

-

Refusals

-

Touching the dog

-

Dog out of control in the ring

For

the purpose of this article, we will look at refusals and think specifically

about those relating to jumping rather than contact equipment. For

the purpose of this article, we will look at refusals and think specifically

about those relating to jumping rather than contact equipment.

Running past a jump or under a pole are

matters of fact. When it comes to a dog not jumping when in a position to do so,

or turning away from a jump, we move into the realms of opinion. At what point

does a dog get into a position to jump? Is it the same for a Large dog as it is

for a Small dog? Does the speed of the dog make a difference? Is the angle of

entry relevant? Do we have to take into account the grade of the dog? Does it

matter if judges interpret a refusal differently as long as each judge is

consistent? To mix the metaphors, it seems like a can of worms in a doggy

minefield.

It would be interesting to get a group of

judges together and observe some possible refusals and see how much agreement

there is between them. Something I tried to do to help me make the decision was

have an imaginary line in front of the jump which would be nearer for Small dogs

than Large dogs. It did not address the issue of grade of the dog and no doubt

other judges would place the imaginary line nearer or further away than I did.

It is, obviously, important for a judge to be

as consistent as possible in marking refusals for a particular class. This still

leaves a problem if the criteria change for a later class at a different grade

or if another judge interprets the refusal differently in the same

circumstances.

Perhaps we should just judge refusals for

running past the line of the jump or going under the pole. That we would get

back to judging them on fact alone. It would then only leave us with the issue

that refusals are penalised differently depending where they occur on the

course. Normally the dog will receive five faults for the refusal and a further

penalty in time taken to correct the error. At the first jump, the dog only has

the five faults because the timer has not started when the fault occurs.

At this point, a lie down in a darkened room

seems to be in order. Maybe I can then give some thought to other areas of

subjective marking in what, until Fred’s voice penetrated my brain, I had

assumed without giving it much thought, was an objectively marked sport.

What Goes Up Must Come Down

Let us

begin by thinking like a judge. Let us

begin by thinking like a judge.

A judge is primarily interested in the dog, not the handler. The sport is

still Dog Agility, not Handler Agility. In order to test the agility of the dog

the course may include jumping round to the right and to the left, with or

without tight turns, to check the flexibility of the dog on both sides. There

may be opportunity for acceleration and deceleration. If you are lucky, the

judge will have built in choices. There might be a safer route, involving an

easier approach to and/or exit from an obstacle to make avoidance of traps

easier. There may also be alternative routes, concerned primarily with saving

time.

The route you get your dog to take round a

course will depend on a number of factors. The first will usually relate to the

ability and experience of you and your dog. You should have identified, in

training, what you and your dog are capable of achieving. The decisions about

the route and handling should be driven by your current skill level as a team.

The time to push boundaries is in training. A competition is the time to test

that training.

Deciding how to run a course can be seen

as an investment decision. The theory argues that there is a link between the

return which can be achieved and the amount of risk you are prepared to take.

Some of us are more cautious and will make decisions which minimise the risk.

Others are high risk takers of the get rich quick type. I guess that most of us

fall somewhere in the middle. Perhaps we have a minimum amount we want to keep

safe at all costs but are prepared to take more risk with anything over that

amount. We can apply this idea of risk being linked to return, to the reading of

an agility course. Which parts of the course are the ones where you decide to

take a least risk approach? Where will you attempt to gain an advantage from a

higher risk strategy. It is about managing the risk profile of the course, with

your investment strategy of minimising faults but posting a competitive time.

This leads on nicely to Isaac Newton,

possibly the greatest ever Englishman, who described the physical property which

is arguably the greatest risk factor in dog agility. In looking at how to run a

course we should be aware of the gravitational pull which is exerted on the dog

and brings it back to the ground. Once a dog has reached the maximum height of

its jump it will begin to be drawn back to earth. This leads on nicely to Isaac Newton,

possibly the greatest ever Englishman, who described the physical property which

is arguably the greatest risk factor in dog agility. In looking at how to run a

course we should be aware of the gravitational pull which is exerted on the dog

and brings it back to the ground. Once a dog has reached the maximum height of

its jump it will begin to be drawn back to earth.

So

what? I hear you ask.

We know that. Yes, I know it is obvious but let's imagine a choice on

the course where a dog can take a slower straight on approach to a jump, or a

faster angled approach to it. With the straight approach, a dog will have less

of its body over the jump for a shorter period of time then with an angled

approach. The more acute the angle, the longer the dog will be over the jump,

allowing gravity to work its magic.

So, next time you walk a course, remember

to check what choices the kind judge has offered you, how they fit into your

investment strategy. Oh, and don't forget Isaac Newton – you might stack the

investment odds in your favour but you can never escape gravity!

As the World Turns, the Dog

Turns

The

other day, I was standing in front of the wash basin watching the water drain

away. My face was covered in bits of toilet paper, drying up the blood after a

not very successful shave. So much for it being the best razor in the world. The

water was swirling around in a clockwise direction. Those of you who studied

physics, will know that means I was in the Northern Hemisphere. More importantly

for me, the water was draining away at a good rate. There was no need for any

tube cleaning. The

other day, I was standing in front of the wash basin watching the water drain

away. My face was covered in bits of toilet paper, drying up the blood after a

not very successful shave. So much for it being the best razor in the world. The

water was swirling around in a clockwise direction. Those of you who studied

physics, will know that means I was in the Northern Hemisphere. More importantly

for me, the water was draining away at a good rate. There was no need for any

tube cleaning.

The way the water drained got me thinking.

It was not a eureka moment, but the cogs had started to turn. I refilled the

basin and let the water go. This time I deliberately swirled the water in an

anti-clockwise motion, but it quickly reverted to flowing clockwise.

It was time to think about the phys-ical

force which was being exerted on the water. Unfortunately, my last physics

lesson had been 57 years earlier and there were huge gaps in my knowledge. I

could have done with some help from Brian Cox, the professor, not the actor, but

as he was not available, I soldiered on, on my own.

What was the strength of the force which I

had observed? I discovered that a litre of water weighs almost exactly 1

kilogram. So, for someone brought up with imperial measurement, the four litres

of water in my basin weighed about nine pounds. Putting this another way, this

mysterious force was turning well over half a stone in weight at a decent speed.

It was obviously something powerful which was at work.

One thing we used to be sure of was that

physical laws are universal. We now know that this might not be an entirely

accurate assumption, but it is good enough to explain the physical world on

which we live. So, if this force works on the water in the basin, it must also

work on people and animals and all other moveable objects on the planet.

Does this mean that it will be easier for

a dog to run and jump in a clockwise circle as it goes with the force which

turned our water in this direction? We all know, or think we know that our dogs

knock more poles down going in one direction than in the other. Is it more

likely to happen when it jumps left (anti-clockwise) than when it jumps right

(clockwise)? Is it also likely to influence the dog's natural line differently?

We really do need our own in- house physicist to sort it out for us.

Think

about reading an agility course Think

about reading an agility course

It is not just handling which has become more sophisticated. Judging has

also discovered the 21st century. Out have gone the obvious traps and sending a

dog out round a jump for no good reason. Now we have greater subtlety with

interesting entries to and exits from obstacles. One of my favourites is setting

jumps either slightly inside or outside the natural line of a turn. Often the

difference is no more than a few centimetres and can be overlooked by handlers,

when walking the course, only for the dog to subsequently run inside or outside

the line. I feel quite smug when this happens, but also a bit sorry. I am just a

softie. I do not like dogs getting faults.

Has any of this got anything to do with

our mystery force, which sends the water from my basin in a clockwise direction?

It must have. So, if there is a physics teacher, agility handler, reading this,

please help us out. In the meantime, I am sure that you will be pleased to hear

that the various shaving nicks have healed. The water is still turning in a

clockwise direction and dogs still run in-side and outside the line of the

jumps. Thank goodness for certainty.

The Air Feels Heavy

The other day, I was standing at the side

of an agility ring. A friend said to me that he was cream crackered. Actually,

he said something that sounded a bit like that, if you get my drift. The reason

for feeling as he did was that the air felt heavy. The other day, I was standing at the side

of an agility ring. A friend said to me that he was cream crackered. Actually,

he said something that sounded a bit like that, if you get my drift. The reason

for feeling as he did was that the air felt heavy.

He said, 'Just look at the

dogs. They are feeling it, too. I have never seen Grade 7 dogs who are so

lethargic.'

I had not noticed anything unusual, but I

had not had my first coffee of the day and was not at my most alert. I watched a

couple of runs and conceded he had a point. The dogs were not performing well,

and the judge was getting a bit twitchy, waiting for the first clear round.

My

friend's symptoms were obvious, even to me, a non-medic. He looked as if the

energy had leached out of him. He described his limbs as heavy and he had a very

bad headache which had come on when the air had got heavy. It was either that or

he had a hangover.

Whether the weather...

Being

a curious sort of bloke, I began to mull over whether we could relate

performance of people and dogs to the air pressure. We only have to watch the

weather forecasts to know that air pressure varies from day to day and that high

pressure is usually associated with a dry spell and low pressure brings the

rain. What I was struggling with was my friend's assertion that a change in air

pressure could have such a devastating impact on his physical wellbeing. I was

not even sure of the parameters in which air pressure changes normally occurred.

It was time to consult Mr Google.

At sea level, air pressure is

approximately 14.7lb per square inch. That seems lot. If you hold your hand out

it does not feel that something that heavy is pressing it down. We also know

that at higher altitudes the pressure is less. Is it just that there is less air

above us? It could not be that simple, could it? Nearly all the athletic jumping

records were set at high altitude so there is clearly some relationship between

air pressure and performance. That was all well and good, but could air pressure

changes, from day to day, in this beautiful field in Derbyshire affect the

health and performance of handlers and dogs?

My research showed that the range between

low and high pressure will not normally be more than 3.5%, which hardly seems

enough to make the air feel lighter or heavier. Perhaps the judge should have a

barometer as well as a measuring wheel and record the pressure before the start

of the class and consult a chart which relates course times to air pressure!!

STOP RIGHT THERE. Scrap that thought. Someone might take it seriously.

My

friend was having difficulty breathing and was looking decidedly grey. My

friend was having difficulty breathing and was looking decidedly grey.

'Let me get you a tea or a coffee, I said?

As we drank, I tried to find out when the air felt heavy.

"On a day like this,

when it is humid and thundery."

That came as a surprise. High pressure is

associated with dry, settled weather. Time for another quick Google. I had an

explanation. Water vapour is lighter than the oxygen and nitrogen molecules

which make up 99% of the air, leading to humid air be-ing lighter.

It still did not explain why my friend

felt worse on a muggy day. Just then there was a flash of lightening in the

distance, followed a few seconds later by a low rumbling noise. At least we now

knew what was affecting the dogs. They must have already heard the thunder. The

sky was turning darker and my friend said the air was getting heavier. It was

looking like there would be an early finish to the day and an instant lake might

even appear in the centre of the field.

The rings were already deserted. The rain

was now torrential. Caravans were steaming up. Wet clothing littered every dry

surface. I suppose we were the lucky ones. It could have been worse. We could

have been sheltering in a car in the day parking. I reflected on my

conversation.

'Jan, do you think the air will feel

lighter after the storm?'' I asked.

All I got was a bewildered look and an

indulgent smile.

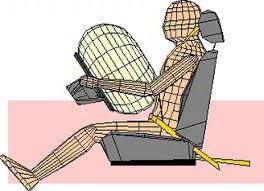

Hit, Run or Airbag

Deployment

I

am sure, that at some time, most of you will have been in a car which as had to

brake suddenly. As the vehicle stops you are thrown forwards and will be restrained by the seat belt. In a more

serious, sudden stop, the air bag might also have deployed, providing a

cushioning effect. The impact on the passenger is normally felt more strongly

than it is by the driver who has, usually, fractionally more anticipation time

and the opportunity to brace for the stop or impact. It can be a terrifying

experience, but what on earth is going on? Why are we thrown forward as the

vehicle stops? To find the answer we have to consult the laws of physics and

Isaac Newton, who is rapidly becoming essential reading for an agility handler. I

am sure, that at some time, most of you will have been in a car which as had to

brake suddenly. As the vehicle stops you are thrown forwards and will be restrained by the seat belt. In a more

serious, sudden stop, the air bag might also have deployed, providing a

cushioning effect. The impact on the passenger is normally felt more strongly

than it is by the driver who has, usually, fractionally more anticipation time

and the opportunity to brace for the stop or impact. It can be a terrifying

experience, but what on earth is going on? Why are we thrown forward as the

vehicle stops? To find the answer we have to consult the laws of physics and

Isaac Newton, who is rapidly becoming essential reading for an agility handler.

Newton's Third Law is about every action

having an equal and opposite reaction. This explains the forward momentum of the

passenger in a car which has to stop suddenly. It also applies to fast running

dogs doing 'hits' on contact equipment. The stop produces the forward momentum

which can lead to the back feet lifting off the equipment and then settling back

on the contact. This negates the supposed advantage of a 'hit' over a running

contact. Going back on the contact during a 'hit' will be an elimination

compared with 5 faults for a missed running contact.

In the small village of Carleton in North

Yorkshire where I was fortunate enough to grow up, if two gardeners on the

allotments agreed that their gooseberries had done well, then it became

universally accepted that it was a good year for gooseberries. It seems to me

that dog agility is a lot like that.

A couple of fast dogs in a Grade 7 Large

Agility class do a 'hit' and lift their back legs on the contact – no, they were

not having a pee. The people in the queue start discussing the issue. A couple of fast dogs in a Grade 7 Large

Agility class do a 'hit' and lift their back legs on the contact – no, they were

not having a pee. The people in the queue start discussing the issue.

- 'It always

seems to happen on 'so and so's' equipment.'

- 'It never occurred when we had

wooden equipment.'

- 'The new equipment has more spring in it, and it is throwing

the dogs off.'

- 'Don't you think it could be the rubber contacts?''

The discussion

goes on and on, almost to the point where they miss their run. By this stage,

the observation of the two dogs has become a universally agreed fact that metal

equipment throws the dog forward during a hit. Goodness knows what will happen

once it gets on social media.

Enough of the speculation. What we know as

fact is that the physical laws of sudden deceleration could cause the dog's back

legs to leave the contact during a 'hit.' Perhaps it really is something worth

studying, using appropriate scientific method. Or perhaps we just need a new

command to inflate an imaginary airbag. That should solve the problem.

This brings us back to the gardeners. They

understand that you have to work with nature to get the best results. Surely

agility cannot be that much different. After all, the laws of nature are

universal. We just need to ensure that we are also working with them and not

against them.

Photo of dog on see saw courtesy of

OneMInd Dogs

Slow, Slow, Quick, Quick,

Slow

It

may not be politically correct, but I have to admit to being a fan of Strictly

Come Dancing. What bloke wouldn't be? You get to watch scantily clad, beautiful

women without being nagged to turn the television off. The real reason for

watching it though is to apply what it can teach us about acceleration and deceleration in agility. Methinks he is telling

porkies! We can, however, discover something about fluidity of movement, change

of pace and direction and balance from the beautifully choreographed routines.

OK, so we can also fantasise about our favourite dancer. It

may not be politically correct, but I have to admit to being a fan of Strictly

Come Dancing. What bloke wouldn't be? You get to watch scantily clad, beautiful

women without being nagged to turn the television off. The real reason for

watching it though is to apply what it can teach us about acceleration and deceleration in agility. Methinks he is telling

porkies! We can, however, discover something about fluidity of movement, change

of pace and direction and balance from the beautifully choreographed routines.

OK, so we can also fantasise about our favourite dancer.

The parallels between dance and dog

agility seem to me to be obvious. In agility, the judge maps out a pattern

which the handler then choreographs. The handler and dog then attempt the

course. The judge waits in anticipation for the perfect round where handler and

dog work together as one and create something new and beautiful. For the judge,

it makes the day. Even Craig would be reaching for his 10 paddle or, I suppose

because it is agility his 0 would be better.

We hear a lot of talk about flowing

courses, technical courses, handler's courses and even impossible courses. In

fact, there are so many adjectives applied to courses that it is difficult to

keep up with the latest theme. A senior judge who had just run one of my Grade

6/7 agility courses, came up to me afterwards and said it was like a jumping

course with contacts. She looked happy, so I took it as a compliment.

The message is

clear

The variety of courses is mind boggling. The way they need to be

choreographed and run is varied. Some will suit your dog better than

others. Remember though, that once the scrimer gives you the cue to go, it is show time and the judge

would love to applaud your run.

Each course will have a natural rhythm.

There will be parts where the dog will need to push on and others where it will

be better to hold back. You will also need to identify the level of effort

needed, bearing in mind the likely need for acceleration and deceleration. Each course will have a natural rhythm.

There will be parts where the dog will need to push on and others where it will

be better to hold back. You will also need to identify the level of effort

needed, bearing in mind the likely need for acceleration and deceleration.

Many

of you will have come across Newton 's

cradle which has five balls suspended in a line. If you let the end one go,

gently, to hit the remaining balls then the one at the other end will move out

gently as well. If two balls are allowed to swing, then two balls will move out

at the other end. The larger the degree of swing and the heavier the contact,

the greater will be the response.

I believe that the underlying principle of

Newton's cradle is directly applicable to handling a dog in an agility ring.

Stronger commands – verbal or body language - are likely to have a greater impact

on the dog than softer ones. So, you have to decide what you want from your dog

and how you are going to achieve it. It sounds easy, doesn't it? Well, perhaps

not that easy.

That still leaves us with acceleration and

deceleration which are merely changes in velocity. Sometimes the shortest route

may not be the fastest, particularly if it involves a tight turn where the dog

has to be slowed down before the turn to avoid running on and then has to build

back up to the optimum momentum. A longer option which enables the dog to keep

up its pace may be preferable. You might want to use a stop watch in training

to try out some examples.

Does Size Matter?

Agility handlers come in all sizes, at

least according to show PA announcers. There are small handlers, medium handlers

and large handlers. At Wallingford we even had Large, lower height handlers.

Perhaps there are a few rugby prop forwards who have taken up agility. Agility handlers come in all sizes, at

least according to show PA announcers. There are small handlers, medium handlers

and large handlers. At Wallingford we even had Large, lower height handlers.

Perhaps there are a few rugby prop forwards who have taken up agility.

It got me thinking. It usually takes a

while to get the brain into gear, but something about the Large, lower height

handlers had struck a chord. Once the grey matter had warmed up, I had a whole

jumble of thoughts going around in my head. I do not know why it happens, but I

do know that it makes my brain hot and it brings on a feverish attempt to create

some sort of order out of chaos.

The crux of the matter seemed to be that

in most sports and even specific positions within the same sport, you need

people of a particular size and shape. Could the same be true of dog agility? If

we were designing a robot to be an agility handler, what would it look like and

what specific skills would you have to build in to its design? We could really

do with a brain storm-ing session but for now you will have to make do with my

initial thoughts.

It is true that agility handlers do come

in all shapes, sizes and age. The most important thing is that they all seem to

enjoy the challenge of handling a dog to the best of their ability. I would not

want anything to interfere with that. Long may we be an inclusive sport. If,

however, we are trying to identify elite handlers, should we be looking for

specific physical characteristics?

Dog agility is not a contact

sport

Did I just write that? I might just have written the agility quote of

the decade. I could be famous. I think it is worth repeating. Dog agility is not

a contact sport. I hear a storm of protest brewing, surely agility is all about

contact. The thing is though, it does not involve any form of physical challenge

with another person, except for the occasional accidental collision with a

judge. Physical contact with the dog is also not allowed and will be penalised

by fault or elimination. The fact that it is not a contact sport might be one

criterion we build into the design of our robot.

I suggest that there are, at least, two

main qualities which we must design into our robot. One is effective

communication with the dog. The robot must be clear and consistent in the instructions

it gives the dog. If we are honest, it is this lack of consistency which often

lets down our agility runs. Unfortunately, at times, we are not even aware that

we are giving contradictory messages. Videos of what we do can help us to

identify problems.

The physical design of our robotic handler

is probably more difficult to get right. You hear handlers say, 'you need

longer legs to do these courses.' I am not sure this is true. Straight line

speed is not primarily what handling is about. Most courses will involve the

handler in making changes of direction, twists and turns and acceleration and

deceleration. This means there is a need for the handler to be well balanced and

flexible.

It is time to consider the physics involved. Better balance will come

from a lower centre of gravity. This points to a shorter person being our elite

handler, but not necessarily with the bulk of our Wallingford prop forwards. A

taller person may have more balance issues than a shorter one and the longer

levers might also be marginally slower to respond to quick changes of movement. It is time to consider the physics involved. Better balance will come

from a lower centre of gravity. This points to a shorter person being our elite

handler, but not necessarily with the bulk of our Wallingford prop forwards. A

taller person may have more balance issues than a shorter one and the longer

levers might also be marginally slower to respond to quick changes of movement.

Perhaps it is time to take the theorising

to the real world. It might be worth looking more closely at some of the most

successful handlers, to see if, by observation, there are specific physical

characteristics they share that contribute to their success. After that, we can continue the development work on our robot. What

year will it be when a robot and dog win an agility class? Maybe we should start

a sweepstake. My entry is for 2030.

After all that, it is time for a lie down

in a darkened room with a cold pack on my head to cool down my brain. If I was a

dog, I would jump in a water trough.

May the Force Be with You

Okay the title is not original, but what do

you expect at these prices. I make no apology for using the phrase, because it

sums very neatly what I have been trying to get across in the series of articles. I am grateful to Ellen for posting them on

Agilitynet and would like to congratulate her on 21 years of wide-ranging

information provision for agility enthusiasts.

Right then, it is time to get back to the

business of science and sport. No one can doubt the contribution of science to

the improvement of sporting performance. It has come in all sorts of guises from

anatomy, nutrition, sports psychology, equipment design, new materials and

training regimes and all the rest you care to mention.

These are what I choose to categorise as

the variable elements of sport science and putting the principles into practice

will often lead to improved performance. We can improve muscle tone. We can

envisage better outcomes. Diet can improve our general health. All this goes for

the dog as well. Okay, maybe it cannot visualise success or perhaps it can!

Agility has had

many changes

Equipment has been standardised and improved. In the early

days, there really was a homemade feel about it. Jump heights have been lowered.

Some obstacles have been removed altogether. Weave gaps have been widened.

Training has become more organised and professional. New ways of handling seem

to be launched almost weekly. Some will stand the test of time. Others will soon

have handlers reaching for the delete button to consign them to the waste bin.

My series of mini articles has not been

about the well-trodden paths which receive widespread coverage on various

forums. I have tried instead to raise a few ideas/issues about the fundamental

laws of nature which cannot be changed and provide the boundaries for our life

on this planet. Your first thought about this is no doubt to question why we

would want to spend/waste time on something which we cannot change. It is a fair

point and until I began to put my thoughts to paper, I thought exactly the same.

I now believe there is mileage in investigating the impact which these

fundamental scientific principles have on our sport.

The laws relating to motion, gravity and

energy transference provide the limits of what is possible. If we do not

understand their impact, we may be setting our sights too low or alternatively

striving for the impossible. You might also want to revisit some of the examples

used in the previous articles. How do we assess the relative gravitational risk

of an acute angled jump, compared with a straight on jump? Is it better to turn

the dog in a clockwise direction if this is an option? Does the law of equal and

opposite reaction always mean that you will need airbag deployment to get a fast

dog to do accurate 'hits' on contact equipment? The laws relating to motion, gravity and

energy transference provide the limits of what is possible. If we do not

understand their impact, we may be setting our sights too low or alternatively

striving for the impossible. You might also want to revisit some of the examples

used in the previous articles. How do we assess the relative gravitational risk

of an acute angled jump, compared with a straight on jump? Is it better to turn

the dog in a clockwise direction if this is an option? Does the law of equal and

opposite reaction always mean that you will need airbag deployment to get a fast

dog to do accurate 'hits' on contact equipment?

I am not a physicist, so I don't know the

answers but there must be someone out there who does. My role has been that of a

naturally curious bystander. In writing this mini-series, I hope that you have

been entertained. I also like to think that I may have pushed you, just a little

bit, to think for yourselves about how science can help your understanding of

the sport you love.

If I see just one reference to anything I

have written, I will be a happy man. For now, I will just enjoy a glass of beer.

I wonder what science has to say about the best way to pick up a pint.

About the

author... About the

author...

Alan Waddington and his wife spend

part of the year in Spain

and the rest in the UK.

He qualified as a judge a few years back

and was busy on the Northern Circuit until health issues meant he could not do a

full day. He has been known to judge in Spain, however, where there is only a

quarter of the dogs we would judge in the UK.

In the UK he does 'sitting down' jobs,

usually scriming.

Published 13th April - 23rd December 2019 |